Over the past few years, a number of negative opinions and misleading information about the front-of-pack nutrition label Nutri-Score (adopted first by France in 2017, and then by Belgium, Spain, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland) have been circulating on social networks, in various media and sometimes even in the words of leading political figures. This phenomenon has been particularly marked in recent months, probably in connection with the current highly publicized debates taking place in the European Community bodies in Brussels to implement a mandatory FOP Nutrition label, based on science, at the European level.

During this bubbling period, the tactics intended to destroy the credibility of Nutri-Score in order to avoid its adoption by the European community appear to be proliferating… Disregarding a convincing scientific record of more than 150 international publications validating its underlying algorithm and its graphical design and demonstrating its efficiency and superiority over other FOP labels on several dimensions of consumer behaviour, and despite its large support by multiple European consumer associations, Nutri-Score is still stongly rejected by certain agro-industry lobbies.

While some manufacturers and retailers in France, Belgium, Spain, Germany, Austria, Portugal, Switzerland, and Slovenia have opted to display the Nutri-Score on their products, strong opposition from major multinational agribusiness companies remains steadfast. This includes large firms such as Ferrero, Lactalis, Coca-Cola, Mars, Mondelez, Kraft, and Unilever. Furthermore, companies like Danone and Bjorg, which initially embraced the Nutri-Score in 2017, have recently chosen to remove it from their branding to safeguard their economic interests—interests that were not addressed by the 2023 update made by scientists.

To undermine the Nutri-Score, food companies are not reluctant to disseminate false information and misleading arguments aimed at discrediting it. These fake news also emerge from various influencers, coaches, gurus and Internet users who give their personal opinions and project in their discourse their personal beliefs, ideologies, and often economic interests rather than evidence-based information. By exaggerating a few details, they seek to undermine the credibility of the entire system.

The misinformation about Nutri-Score currently circulating on social networks and in some media are clearly different from the legitimate criticism that is part of a useful scientific debate (particularly on the limits of the system), both in their objectives and in their form. False news is characterised by the fact that the information it conveys is misleading, and only seeks to raise confusion. They are often limited to the juxtaposition of examples that may each taken alone be right but which staging may contribute to sow doubt among those who do not have sufficient knowledge about the Nutri-Score, and in particular how it is calculated and used.

Fake news therefore highlights a single example– and often enough a peculiar one – , taken out of any context, using it to discredit the whole system. They then circulate in the same form (message or visual document), usually through a powerful image presented in a pseudo-scientific form. The same image is often accompanied by contemptuous or even insulting comments. Fake news are often put online or relayed by « anonymous » users or by individuals who rely on the same information (often the same image) to give their personal opinion (in some cases probably deceived themselves by the information or insufficiently informed to recognize the fake news). What is spectacular is that this misinformation ends up being taken up as scientific elements by some media (even well established ones) and by all those who have an interest in using it (lobbies, scientists with links of interest with economic operators, political personalities, even ministers, etc.).

The launch of false information about the Nutri-Score and the fact that it is relayed by different issuers imply different mechanisms:

- the uptake of examples of comparisons of the Nutri-Score on a very limited number of foods, always the same, which are displayed together and staged in order to give the impression that the Nutri-Score would classify absurdly the nutritional quality or the health value of foods, and therefore mislead consumers… It is interesting to note that the examples used are always based on the same brand name foods (less than 30 brand foods – displaying the initial and not the updated version of Nutri-Score – while more than 200,000 products may be used to calculate and show the Nutri-Score) and which are intended to impress people using their popular perception (traditional foods deemed to be healthy, industrial foods deemed to be unhealthy, etc.) and by binary comparison (well or badly classified).

- The lack of knowledge or the denial of what can be expected from Nutri-Score (or any other front-of-pack nutrition label). Thus, either voluntarily or not, they clearly do not incorporate the the principle, the objective, the constraints and the scope of action of a nutritional logo, neither the set of scientific data pertaining to the validation of its computational algorithm or its graphic format (as described in : https://nutriscore.blog/2025/09/20/the-nutri-score-nutrition-label-justifications-scientific-basis-user-guide-benefits-limitations-deployment-and-update/).

Below are presented various fake news that regularly appeared on social networks and for which we explain their lack of seriousness.

1. Example of fake news based on a real misunderstanding of the purpose of Nutri-Score

“Nutri-Score has no interest and is misleading to the consumer, the proof is that some ultra-processed foods containing additives or pesticides are well classified with Nutri-Score !”

This kind of criticism relates to the fact that Nutri-Score does not include additives, degree of processing, or pesticides. This choice is fully assumed for Nutri-Score as for all other FOP nutritional label (for more details see articles: https://nutriscore.blog/2021/11/28/nutri-score-and-other-health-dimensions-of-foodshow-to-better-inform-consumers/; https://nutriscore.blog/2020/11/07/nutri-score-and-ultra-processing-two-dimensions-complementary-and-not-contradictory/), and is linked to the impossibility, given current scientific knowledge, of developing a synthetic indicator covering all the different health dimensions of foods. This point is not specific to Nutri-Score, it is the case for all nutritional labels existing in the world (Chilean warnings, Australian HSR, British Multiple traffic lights, Italian Nutrinform batteries,…).

Nutri-Score refers to a nutritional information system, which has been shown to be very useful in helping consumers to be aware of the nutritional quality of foods and to direct their choices towards foods of higher nutritional quality. But under no circumstances does Nutri-Score claim to be an information system on the global ‘health’ dimension of food covering, in addition to the nutritional dimension, the health and environmental dimensions.

To summarize the overall health dimensions of food (nutritional composition, ultra-processing/additives, pesticide residues) through a single and reliable indicator, which would be able to predict overall health risk would be, obviously, the dream of any public health nutrition actor in the interest of consumers. But it is not by chance and certainly not by incompetence, if no international research team or public health structure in the world, or any committee of independent national or international experts, nor has the WHO, been able to develop such a synthetic indicator. This can be explained by several reasons:

1) First, the level of evidence concerning the links with health differs according the dimension considered for food. The accumulation of numerous epidemiological, clinical and experimental studies provide for certain nutritional components (nutrients/foods) a documented and robust level of evidence of their impact on chronic disease risk ranging from “probable” to “convincing” in international classifications. For the other dimensions, in particular those referring to numerous additives, neoformed compounds or contaminants (pesticides, antibiotics, endocrine disruptors, etc.), while some strong hypotheses of their impact on health have been raised, their underlying levels of evidence differ greatly (especially in terms of human studies).

On the other hand, the association between consumption of ultra-processed foods (NOVA4) and the risk of chronic diseases is documented by numerous prospective epidemiological studies (including those of the research team that developed Nutri-Score).

2) As a result of the above, it is currently impossible to weight the relative contribution of each dimension of a food, to provide a synthetic score that would ideally be predictive of an overall health risk level. Some apps may offer it, but they have no valid and robust scientific basis. The methodological questions are numerous and still unresolved: precise measurement of the risk attributable to each of the dimensions, to each of the various components potentially incriminated, potential cocktail effect, etc. In fact, calculating a single index to characterize the overall health quality of a food, which could ultimately lead to an absolute judgement is not based on sufficiently solid scientific bases and is therefore rather arbitrary.

Finally, with regard to additives and pesticides, where there is a sufficient body of evidence for a health risk, the answer from a public health point of view is not the information of the consumer through a logo, but the removal of the element in question from the food chain, according to a health risk management principle. This is the case today for the controversial additive E171 or nitrites, for which a withdrawal is justified.

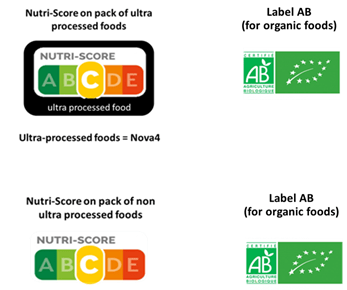

However, if the different health dimensions of food (nutritional composition, ultra-processing/additives, pesticide residues) cannot be combined in the same algorithm underlying a single label, it is possible (and necessary) to provide to consumers specific information on all these points. As part of an effective public health nutrition policy, it is possible to recommend, as it is done in the food-based dietary guidelines available for the general population, to choose foods with the best Nutri-Score, without or with the shortest list of additives (in the list of ingredients) and to prefer unprocessed foods and, if possible, organic (with a certifying label). Scientists who developped the Nutri-Score proposed to combine the information on these different dimensions in graphic form. This is doable, even if there are still practical points to solve, by adding around the Nutri-Score, a black edge for the ultra-processed foods; and by adding for organic foods, the corresponding official label (https://nutriscore.blog/2021/11/28/nutri-score-and-other-health-dimensions-of-foodshow-to-better-inform-consumers/)

A randomised controlled trial performed on more than 20,000 subjects demonstrated the interest of this front-of-pack label combining the Nutri-Score (informing on the nutrient profile dimension) with an additional graphic mention, indicating when the food is ultraprocessed, compared with a no-label situation. Results showed that this combined label enabled participants to independently understand these two complementary dimensions of foods. It strongly improved the ability of the participants to detect food with better nutritional quality and to identify UPFs and to impact on purchasing intentions and the products perceived as the healthiest, towards a better nutritional quality and a reduction of UPFs (https://nutriscore.blog/2022/12/24/a-randomised-controlled-trial-demonstrates-the-interest-to-combine-nutri-score-with-a-black-ultraprocessed-banner-to-independently-understand-these-two-correlated-yet-distinct-and/).

Finally, although Nutri-Score only focuses on the nutritional information of consumers, this already represents a lot in terms of public health, as demonstrated by the prospective cohort studies (some involving more than 500,000 people followed for more than 15 years), which show at the individual level that the consumption of foods that are well classified by Nutri-score is associated with lower mortality and a lower risk of developing chronic diseases: cancer, cardiovascular disease, obesity,etc. I

2. An example of fake news based on pseudo contradictions in the ability of Nutri-Score to classify foods according to their nutritional qualities

“Nutri-Score is false, the proof: fries that are not good for health are better ranked than sardines that contain lots of good components; or olive oil is less well ranked than

Coca-Cola zero…!”.

We have to keep in mind that the purpose of a FOP nutrition label such as Nutri-Score is not to classify foods as “healthy” or “unhealthy”, in absolute terms, as a binary nutritional label would do (good vs. bad). Such a purpose for a nutritional label remains totally questionable since this property is linked to the amount of food consumed and the frequency of its consumption, but also to the overall dietary balance of individuals (a nutritional balance is not achieved on the consumption of a single food item, nor on a meal or even on a day…). These complex concepts cannot, of course, be summarized by a nutritional logo attributed to a specific product of a given brand…

The real purpose of Nutri-Score is to provide consumers with information, in relative terms, that allows them, at a glance, to compare easily the nutritional quality of food, which is already a very important point to guide their choices at the time of the act of purchase. But this comparison between foods is of interest only if it is relevant, especially if it concerns foods which the consumer needs to compare in real life situations (at the time of his act of purchase or his consumption). Moreover, by definition, the Nutri-Score does not invent anything. It simply reproduces in a synthetic form the elements of nutritional composition that appear on the mandatory nutritional declaration at the back of the package.

And on the contrary, fake news will try to divert the interest of the Nutri-Score by highlighting pseudo-contradictions based on non relevant comparisons of specific foods… For instance, here is one of the pictures that circulates most often on social networks that are widely promoted by Internet users, certain media, lobbyes and politicians.

First, some of the Nutri-Score presented on this picture are false (or do not take into consideration the update of the Nutri-Score published in 2023): for instance, those french fries are B (and not A); same for this breakfast cereals in fact ranking B and not A. Diet coke is C and not B; olive oil is B and not D…

Moreover, the principle of this picture (shared many times in the social networks) is to caricature the Nutri-Score suggesting that certain categories of industrial products would be classified as « healthy foods » and better ranked than “traditional” foods that would be considered “unhealthy” (“Unhealthy foods”).

Nutri-Score makes it possible to compare the nutritional quality of foods, but on condition that these comparisons are relevant and useful to consumers to guide their choices :

a) the Nutri-Score allows for comparing differences in nutritional quality among foods belonging to the same category.

For example, within the breakfast cereals category, one can compare mueslis or granolas versus chocolate cereals, versus chocolate-filled cereals… (with Nutri-Scores ranging from A to E).

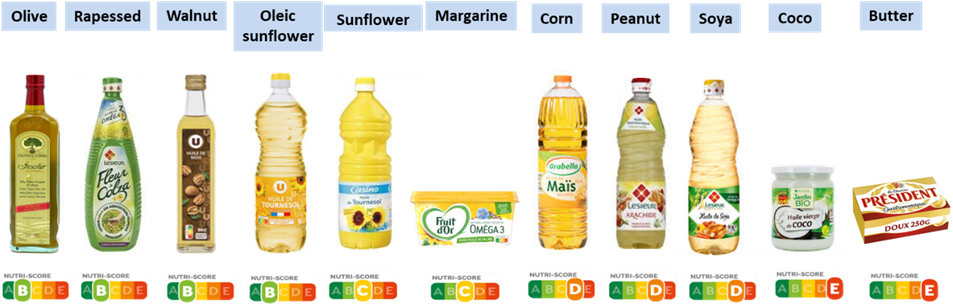

Within the category of added fats, recognizing the differences in nutritional quality among olive, canola, walnut, sunflower, peanut, coconut, and palm oils, as well as margarines and butter (ranging from B to E).

Or, within ready-made dishes, comparing the differences in nutritional quality of meat lasagna with those made with salmon, tuna, spinach, vegetables, or many other ready-made dishes based on pasta or other ingredients (with variations in nutritional quality ranging from A to E). For example, the Nutri-Score allows for recognizing the nutritional quality differences among the many types of pizzas or savory tarts (which can vary from B to E):

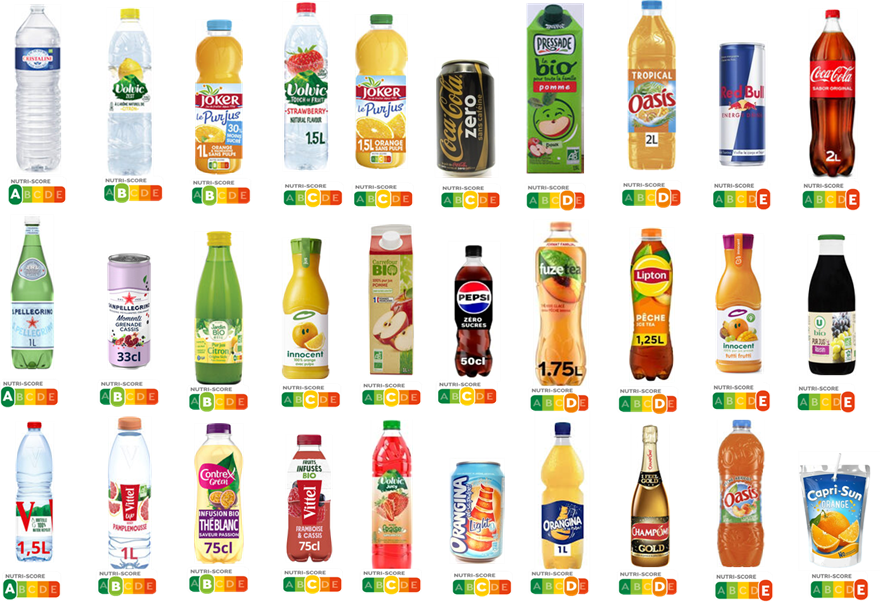

Another example: within the beverage category (plain or flavored water, fruit juices, fruit-based beverages, sodas, dairy-based drinks, plant-based drinks, etc.), being able to easily assess the differences in nutritional quality (with Nutri-Scores ranging from A to E based on sugar content and/or the presence of sweeteners).

In each category, there are several Nutri-Score classes, which provides useful information for consumers’ choices.

b) The Nutri-Score also allows for comparing differences in nutritional quality for the same food offered by different brands.

For example, comparing chocolate mueslis from one brand with its “equivalent” from another brand bearing the same name.

Or comparing “cordon bleu” escalopes or cassoulets offered by different brands but with the same designation.

Once again, differences in nutritional quality for products with exactly the same name, and therefore often not obvious, can be easily highlighted thanks to the Nutri-Score.

c) The Nutri-Score also allows for comparing differences in nutritional quality among foods belonging to different categories but having the same usage conditions, purposes, or intended consumption (and which are often located in the same supermarket aisles or nearby sections).

This is notably the case for foods that are typically consumed at the same time, for the same occasion of eating, or that are used for the same purpose and therefore may compete and substitute for each other at the time of food purchasing decisions. For example, this applies to foods that can be consumed as an appetizer/starter: the consumer may need to choose between foods in the category of raw vegetables or others in the category of charcuterie, spreadable salted products, or soups/broths. Similarly, for various foods that can be consumed during an aperitif: savory snacks, raw vegetables, spreads, dried fruits, or canapés.

Comparison of different foods from various categories that can be consumed during an aperitif *,**

*There is also variability in nutritional quality within each of the categories of foods typically consumed at an aperitif: for instance, while the Nutri-Score allows for comparing chips to dried fruits or charcuterie, the label also highlights differences in nutritional quality within the chips, which can vary in composition from B to D (depending on their salt and fat content); for dried fruits, it can vary from A (for natural forms) to E (for salted forms); and for spreads, it can range from B to D depending on the types.

**If today only certain pre-packaged raw vegetables (notably tomatoes) display the Nutri-Score, it’s important to keep in mind that with its planned expansion in 2025 to raw products, all fruits and vegetables sold loose will be able to display the Nutri-Score.

The same reasoning applies for comparing foods consumed for dessert: between the categories of fruits, dessert creams, yogurts, pastries, or ice creams and sorbets.

Similarly, for foods purchased to be consumed at breakfast, where the consumer may be prompted to choose between breads, toasts, breakfast cereals, biscuits, and industrial pastries.

Therefore, the Nutri-Score indeed allows for comparing the nutritional qualities of foods from different categories, as long as the comparison is relevant. This is, in fact, what consumers intuitively do during their shopping. For example, when grocery shopping, they do not question whether they should choose between breakfast cereals and olive oil or between sardines and soda. It is highly unlikely that a consumer would consider having a bowl of olive oil for breakfast, using breakfast cereals to season their salad, or quenching their thirst with canned sardines…

So, this type of fake news gives the feeling that the Nutri-Score is not consistent in terms of nutritional classification of foods only by comparing foods that have no reason to be compared with each other while omitting the main interest of the Nutri-Score for the consumer, namely, comparing foods under relevant conditions. The other element of deception underlying the fake news is based on playing with stereotypes in terms of food belief or perception.

The image of French fries (often linked to fast-foods) is, in the popular belief, rather perceived as unfavorable from a nutritional point of view, while that of “traditional” foods such as Roquefort, Serrano ham or sardines (just like smoked salmon) have a rather favourable perception. Yet it is enough to look at the nutritional declaration on the back of pack of these foods to realize the reality of the nutritional composition. It is quite normal that Roquefort or Serrano ham should be classified E, given their very high content in saturated fats and salt. In the same way that smoked salmon is classified as D, which is widely used as a critique of Nutri-Score, is quite « normal » given its salt high content (2.5 to 3.5 g of salt per 100 g), unlike fresh salmon, which is classified as A, which is never indicated in the fake news mocking the classification of smoked salmon by Nutri-Score.

Again, there are very large differences in nutritional quality within the food categories (different cheeses, different hams, etc.) or for the same food depending on the preparation and brand. If Roquefort is classified in E (it contains a high quanity of salt and saturated fats), the majority of cheeses are classified in D and some in C (for example mozzarella). Even for ham, for example Serrano ham can be E or D (depending on the brand), and other types of ham are classified in D or C.

For sardines, widely used in fake news to question the interest of Nutri-Score (always through the same image of the same brand), if some brands are actually classified in D, other canned sardines will go from A to D according to their nutritional composition. So we can see that is not honest to suggest that sardines are systematically classified in D by the Nutri-Score…

Specific problems with French fries

Remarks made in the fake news about French fries imply both irrational perception of this type of food (negative image linked to fast-food) and there, again, on the misunderstanding of how a nutritional logo is established and what its role can be. Indeed, by definition, the Nutri-Score (like all other FOP nutrition labels) is, in fact, only a translation of the declared nutritional values present on the back of the package, which refers to foods as sold. The manufacturer is required to be transparent about the nutritional composition of foods which are placed on the market, but the latter cannot take into account and/or anticipate the variability of the methods of preparation, use or consumption for its product. For Nutri-Score, only foods that require a specific reconstitution, according to a standardized recipe (mashed potatoes flakes, dry preparations for cakes), have to give a Nutri-Score calculated on the basis of the standardized recipe.

However, for frozen French fries several cooking methods are possible. Cooking in the oven frozen pre-cooked fries (usually classified B by Nutri-Score) has no impact on the nutritional composition, so the Nutri-Score is not modified in this case after cooking (it remains B). On the other hand, for frozen French fries (not pre-cooked) usually classified A by Nutri-Score (they are simply peeled and cut potatoes), the cooking method information given on the packaging recommends using a fryer. Under these conditions, the Nutri-Score will change, depending on the cooking oils (more or less rich in saturated fatty acids) from A to B or maximum to C. The subsequent addition of salt may also affect the note, but cannot reasonably be anticipated upon purchase of the product. These elements show both the interest of Nutri-Score, which helps to inform consumers on the reality of nutritional composition and to combat certain stereotypes or misconceptions: in the example of French fries widely used in fake news, those pre-cooked have rather a favourable nutritional composition and even those not pre-cooked remain nutritionally correct even using a fryer (classified B or maximum C). However, it appears necessary in the case of foods that cannot be consumed as purchased (such as frozen, uncooked fries), and only for those which a specific and detailed method of cooking is given on the packaging that could impact the Nutri-Score, that the manufacturer alerts consumers to the modification induced on the Nutri-Score. As part of the recommendations, it is requested that the manufacturer inform consumers of the modification induced on the Nutri-Score by indicating on the package the generic phrase “When cooking in a deep fryer, the Nutri-Score of the product may be degraded by one or two letters.”

Finally,

It is clear, contrary to what fake news conveys, that Nutri-Score makes it possible to distinguish easily, at a glance, the nutritional quality of foods and to compare foods with each other, to help consumers to choose a more nutritionally favourable alternative either in another category corresponding to the intended use of the food, either in the same category by choosing a better Nutri-Score or the brand offering the best-ranked food.

It is also essential to remind a major rule of Nutri-Score, which never appears in fake news: the fact of being classified D and E for a food does not mean that it should not be consumed at all. In the context of a balanced diet, it can be integrated but the informed consumer will know, if he does not wish to choose an alternative of better nutritional quality and wishes to maintain his choice for a product D and E, it is better to consume it in smaller quantities and/or less frequently.

Is the classification issued of the specific foods displayed in the fake news, such as the comparison between olive oil and zero Coca-Cola, specific to Nutri-Score? How do the other logos classify them?

As all FOP nutrition labels are based on the data corresponding to their nutritional composition, all colour-coded logos such as the Traffic Light in the United Kingdom or the ENL supported by certain international food companies, describe two “red” messages for olive oil based on its saturated and total fat composition, whereas zero Coca-Cola has 4 “green”. Similarly, in the case of health warnings endorded in Chile, Canada or Israel, Coca-Cola zero displays no warnings. So whatever the system, olive oil is less well-classified than Coca Cola Zero given its content in calories, total fats and saturated fats. But curiously if this criticism is raised strongly for Nutri-Score, no one was ever offended by this classification for the British Traffic Lights Multiples and this did not pose any problems for consumers of the retailers that already use for many years this type of logo (in United Kingdom, Spain or Portugal) and also place with their system, olive oil worse than Coca-Cola zero.

Finally, very often, among the fake news circulating, it is disseminated that olive oil is ranked D by Nutri-Score. In fact, since 2019, it was ranked C (the best ranking for added fat) and moved to B in 2024 following the recommendations of the European Scientific Committee in charge of the update of the Nutri-Score.(https://nutriscore.blog/2022/08/04/report-of-the-european-scientific-committee-in-charge-of-updating-the-nutri-score-changes-to-the-algorithm-for-solid-foods/).

And soda with sweeteners are now classified C by the update version of Nutri-Score (and not B).

4. Fake news about the fact that the Nutri-Score would be appropriate to France and not to other European countries

« The Nutri-Score is purely French and not adapted to other European countries. As a matter of fact, the adjustments made in his calculation were made to please his cheese sector»

Another fake news circulating on the internet is the fact that France made a specific exception on the calculation of the algorithm for cheeses in order to improve the image of French cheeses that are part of its culinary heritage! This is of course totally wrong. In fact, during its development in 2015-2016, the Nutri-Score underwent marginal adjustments that did not change the elements taken into account for the calculation of the final score which allows to assign the different colors of the Nutri-Score to foods. The « negative » elements of the calculation are those which are included in the mandatory nutritional declaration at European level and which are mentioned in the mandatory labelling on the back of the packaging (calories, total fat, saturated fat, sodium, which are otherwise the only elements available for all foods). Minor adjustments to the method of calculation were realized by the French High Council for Public Health for cheeses, added fats and beverages.This comes from the fact that after the analysis in 2015 of the French Food Safety Agency (ANSES) these 3 categories (these are indeed categories no specific foods) have been recognised as raising specific problems that were easy to solve (without calling into question the choice of nutrients used in the calculation of the algorithm):

- For cheeses, because of their high saturated fatty acid composition, the protein content (used as a proxy to reflect the calcium and iron content of foods in the Nutri-Score calculation algorithm) was not integrated in the calculation of the score underlying the Nutri-Score. So all cheeses were ranked in E. Yet, cheese is an important source of calcium. As a result, it was considered that the algorithm presented an inconsistency, since it did not take into account the contribution of cheese to calcium intakes. Similarly,the initial calculation did not permit to distinguish differences in salt and/or fat content. With the change, the vast majority of cheeses (French or not) are classified in D (which is consistent with the nutritional recommendations that aim not to push to overly high cheese consumption), going further from C (for low-salt fresh cheeses) to E (for salted ripened cheeses).

2. All the added fats were classified in the same Nutri-Score category, but it was clear that it is relevant to discriminate between animal fats richer in saturated fatty acids (such as butter) and vegetable fats less rich in saturated fats (oil, margarines), consistent with food-based dietary guidelines for the general population. The modification made to the algorithm permits to discriminate between the two groups since animal fats are all in E (with palm and coco oil), unlike vegetable oils and vegetable margarines which are better classified (in D or C).

3. For beverages the change made to the original algorithm was related to the fact that beverages have a different density from solid products, and that most contain mainly sugar. Adaptation was carried out mainly to ensure that water was the only drink classified as A (and to prevent sweetened drinks from being classified at the same level as water, given the components taken into account in the calculation).

5. What lessons can be learned from these food comparison problems conveyed by fake news

Even if, as previously mentioned, the (not justified) comparison of nutritional scores of certain foods is not adapted and appears as an irrelevant criticism in terms of practical reality (like comparisons between Coca-Cola Zero and olive oil ), and although Nutri-Score works perfectly for the very large majority of foods, the nutritional positioning of a limited number of foods in the Nutri-Score scale (related to the calculation of its basic algorithm) nevertheless raises real issues in terms of public health which the scientists working in the design of the system since its inception are fully aware of. Even if they are not of the same nature as those raised by fake news, some elements concerning the positioning of some rare foods with regard to public health recommendations require a short or medium-term reaction:

– For olive oil, it is not so much an irrelevant comparison with other foods (which have nothing to do in term of use) which is a real problem, but olive oil is, of course, better placed than animal fats (classified E) or very rich oils in saturated fatty acids (coconut, palm, etc.). Its ranking is consistent with the nutritional recommendations of public

Olive and nut oils were initially classified in C as rapeseed oils among the three best-classified oils … And the scientific committee in charge of updating the Nutri-Score proposed that olive oil be classified in 2023, in B, as rapeseed oil and walnut oil (https://nutriscore.blog/2022/08/04/report-of-the-european-scientific-committee-in-charge-of-updating-the-nutri-score-changes-to-the-algorithm-for-solid-foods/).

– For sweeteners, it the update of Nutri-Score in 2023at European level in 2021 classified the beverages containing sweeteners in C (and D or E, if they contain sweeteners and sugar).

Answers to other fake-news concerning Nutri-Score may be found on different articles:

Nutri-Score and Ultra-Processing: two dimensions, complementary and not contradictory

Nutri-Score: science to demystify fake news

Moreover, it should also be clearly pointed out that Nutri-Score, like all FOP nutrition labels, is only one of the elements of a public health nutritional policy. It must benefit from educational support (information, communication and education for the general public, health professionals, social workers, education, etc.) as regards its use, its meaning, its interest and its limits. It is complementary to other public health measures and in particular all communication actions on generic consumption recommendations in terms of unprocessed food and products containing as few pesticides as possible (organic foods).

CONCLUSION

Finally, a debate around the Nutri-Score is legitimate and it is important for everyone to be able to make their voice heard and to be able to ask questions (scientists, consumers, industrialists, journalists, specialists or laypersons, etc.), but it is important that the debate remain constructive and honest. The Nutri-Score, both in its construction and its validation, is based on a very solid scientific basis (with more than 150 scientific publications in international peer-reviewed journals) demonstrating its effectiveness and superiority over all other FOP nutrition labels (which do not have such a compelling scientific record).

Through focused and disproportionate criticisms denying the multiple interests of Nutri-Score, the lobbies’ strategy aims only to prevent the deployment of Nutri-Score in Europe… to maintain the status quo, which remains unconvincing and of little use to the consumer.

***********

Serge Hercberg1,2, Pilar Galan1, Manon Egnell1, Chantal Julia1,2

1 Université Paris 13, Equipe de Recherche en Epidémiologie Nutritionnelle (EREN), Centre d’Epidémiologie et Biostatistiques Sorbonne Paris Cité (CRESS), Inserm U1153, Inra U1125, Cnam, COMUE Sorbonne-Paris-Cité, F-93017 Bobigny, France

2 Département de Santé Publique, Hôpital Avicenne (AP-HP), F-93017 Bobigny, France