As scientists working and publishing in the field of public health nutrition and especially on front-of-pack nutrition labelling (FOPNL) for more than a decade, we have read with concern the paper “Publication bias and Nutri-Score: A complete literature review of the substantiation of the effectiveness of the front-of-pack logo Nutri-Score” published by S. Peters and H. Verhagen in Pharmanutrition https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213434424000069?via%3Dihub

This article is riddled with inaccuracies, inconsistencies and errors . The text presents biased arguments leading to erroneous conclusions. As such, it does not meet the standards of a true scientific article. In fact, using the appearance of a scientific article, it is a pamphlet written by two authors that work for industry trying to cast doubt on academic science and to make serious accusations toward public research teams to discredit the front-of-pack nutrition label Nutri-Score.

It is important to remind that Stephan Peters and Hans Verhagen are working for organizations that have been involved in lobbying against Nutri-Score for many years. Stephan Peters is employed by the Dutch Dairy Association, a trade organization representing 13 members such as the Dutch branches of Arla, Friesland Campina, Royal Lactalis… which are strong opponents to Nutri-Score and constant detractors of academic science about Nutri-Score. Hans Verhagen is the owner and consultant of Food Safety & Nutrition Consultancy (that includes the European Association of Sugar Manufacturers among its clients). Dutch dairy product Associations (such as the European Dairy Association) and sugar manufacturers are harsh opponents to Nutri-Score and have already provided funds to publish narrative reviews (not original data) aiming to « reinterpret » results of original academic studies that disturb their economic interests.

Therefore, the paper published by Peters and Verhagen (with conceptual and methodological problems, wrong classification of scientific papers, biaised arguments, accusations of scientific misconduct and false statements,… ) aims to cast suspicion on academic public researchers and on the studies they published in peer-reviewed journals with the final objective to discredit Nutri-Score, a public health tool that is disturbing the interest of food companies (dairy products, especially cheeses; processed meat; food and beverage products which are high in saturated fat, salt and sugar…). This paper mainly targets the scientific article recently published in BMJ Global Health by Besançon S. et al (https://gh.bmj.com/content/8/5/e011720.full) that showed that 1) of 134 articles investigating the effectiveness of Nutri-Score, 83% had conclusions favourable to this label demonstrating the relevance of its algorithm, better performances vs other nutrition labels, an impact on food choices and on the nutritional quality of food purchases; 2) the probability for an article to show results that are not favourable to Nutri-Score is 21 times higher if the authors declare a conflict of interest or if the study is funded by the food industry and 3) three private organizations were particularly involved in the funding (or conflicts of interest of authors) of studies not favourable to Nutri-Score and among them, the Dutch Dairy Association (for which Stephan Peters is working).

A paper aiming to cast the doubt on academic research studies that demonstrated the interest of Nutri-Score

The paper published by Peters et Verhagen tries to cast suspicion on the studies developed by academic research teams they accuse of “conflict of interests” on the pretext that their scientific work led to the development of the Nutri-Score a few years ago (in 2014). They extend this notion of conflict of interest to all teams developing collaborations with them! Their idea is to try to “disqualify” the scientific work produced by the academic research teams considering that their involvement with the development of the Nutri-Score and its subsequent validation is a conflict of interest! It is particularly obvious with the terms they use to characterize the research teams they want to discredit. They don’t use the real academic affiliation of the French Research Team whose scientific works permitted to create Nutri-Score which is “Nutritional Epidemioloy Research Team (EREN) or research team of the National Institute for Health and Medical Research/ National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment / Sorbonne Paris Nord University. They use the term of “developers of Nutri-Score” or “the scientific group around the developers of Nutri-Score that have published scientific articles…”. Regarding the research teams who were associated in collaborative studies with EREN, they use the misleading (even pejorative) term “authors who are employed or connected with its developers”. It is obvious that EREN research team does not “employ” the academic research teams with which it collaborates! These terms are deliberately used to trivialize and discredit public research teams.

Throughout the paper of Peters and Verhagen, it appears that the real objective of the authors is to minimize the link between economic conflict of interests or funding for studies coming from food industry actors (as those Peters and Verhagen are working for), highlighted by the scientific publication of Besançon et al, and to try to introduce other criteria to disqualify real scientific studies that are favourable to Nutri-Score. Even more incredible, Peters and Verhagen intentionally do not integrate in their analysis the economic conflicts of interests of authors, or funding that are behind some papers while it is a crucial point! They do not account for these conflicts in their classification of the papers and in their analysis. They totally deny in their introduction, analysis, results and discussion this major point even if this kind of conflict of interests (COI) has been demonstrated to influence the results of studies (they just quote the main results of the Besançon’s paper without discussing the important role of financial COI).

Denying the economic conflicts of interests behind papers with unfavourable results about Nutri-Score, they only choose to disqualify papers showing favourable results for Nutri-Score published by the academic researchers that developed Nutri-Score and performed validation studies only with public funds, and sometimes in collaboration with other academic research teams or public institutions (WHO, IARC,…). Peters and Verhagen try to discredit these studies considering that they would present some « conflicts of interest » even if the academic research team that has participated in the development and validation of the Nutri-Score is composed of independent experts from academic and national research institutions working extensively on the subject of front-of-pack labels for several decades and on many other public health topics regarding the relationships between nutrition and health. These experts develop their research without any profits, only working for public health ! It is clear that to minimize the fact that they defend economic interests, Peters and Verhagen suggest that the academic researchers who developed Nutri-Score and the academic research team associated in some collaborative studies have “conflicts of interest”. Using this fallacious definition they classify the articles to support their objective to discredit the science behind Nutri-Score.

A paper full of inaccuracies, inconsistencies, errors and biased arguments leading to erroneous conclusions

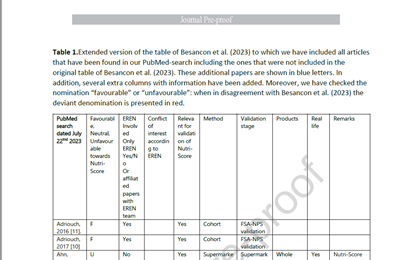

Peters and Verhagen attack the quality of the study performed by Besançon et al using fallacious arguments. They lay serious accusation about the quality and exhaustivity of the database published by Besançon et al, particularly suggesting that this database lacks papers unfavourable towards Nutri-Score. They emphasize the fact they have found papers in their PubMed-search that were not included in the original table of Besançon. These additional papers are shown in blue in Table 1 (see below). They use this argument to discredit the Besancon’s study, with the underlying that Besancon et al. intentionally excluded these papers from their database as they are unfavourable towards Nutri-Score…. In fact, this is a false statement. Peters and Verhagen added 40 publications (in blue in Table 1; 39 of these papers were published at the end of 2022-2023, i.e., after the period covered by the search for references in the Besançon study (covering the period January 2014-November 2022). The only study missing in the Besançon database corresponds to a study performed by Vandevijere in 2021 (ref 100 in Table 1), however this study did not test the original Nutri-Score but a black and white version of Nutri-Score not displayed on the FOPNL but on electronic shelf labels.

On the other hand, the methodology of the paper of Peters and Verhagen presents major problems in term of inclusion and exclusion criteria, classifications of papers as “Favourable / Neutral / Unfavourable” to Nutri-Score, number of studies really included and definition of “conflict of interest”.

1. Discrepancies and inconsistencies in inclusion and exclusion criteria

Table 1 presents some errors and inconsistencies with the text, especially in the count of papers included in the analysis. In the “Chapter 2. Materials and Methods, Part. 2.1 Literature search”, it is announced that 180 papers were identified from the PubMed database (searched on 22 July 2023). But counting the number of papers presented in Table 1 there are only 175 papers, from which 15 are indicated as “not found in PubMed” (but probably found in the paper by Besançon et al. 2022). So, out of the 180 announced papers, we have information only on 160, but in fact 159 because there is an error regarding the paper by Bonnacio et al. (2022) – it is presented twice in Table 1 (with 2 different references: 107 and 156 and, curiously, with 2 different classifications for the same paper: Favourable when cited with the ref 107 and Neutral when cited with the ref 156).

And additional confusion in the counting of articles included in the analysis is linked to the fact that in chapter 3.1. Favourable versus unfavourable, Peters and Verhagen gave the summary of the papers included in their analysis (with references) as 63 papers marked as Favourable “conducted by authors who are employed at or connected with its developers” [6,7,9-69] and 4 marked Unfavourable [12,49,70,71]. Next, there are 37 papers marked as Unfavourable to Nutri-Score [4,5,49,70-103] “conducted by authors who are not employed at or connected with its developers, 17 papers marked as Favourable [104-120], and 14 papers marked as Neutral (not favourable or unfavourable [92,102,121-132]).

So the grand total is: 63 + 4 + 37 + 17 + 14 = 135. We can see some inconsistencies in this selection (for example ref 92 is cited as neutral but is also included in the range of papers 70-103 indicated as unfavourable)…

Subsequently, Peters and Verhagen state that they have selected from these papers those they considered relevant for different validation stages of Nutri-Score according to the validation stage information in Table 2. They finally selected 104 papers presented in Table 2. However in Table 2 many papers are absent from the above references. It is the case of the papers referenced as 139-175.

There is also no indication about the inclusion criteria used by the authors to consider which papers are relevant for the validation of Nutri-Score (indicated in Table 1 and included in the analysis). These points are not detailed in the text and seem totally arbitrary and based on a personal decision of authors.

Mostly, papers favourable to Nutri-Score are considered as not relevant for validation of Nutri-Score and excluded of the analysis, pointing to a potential classification bias.

Moreover and curiously, some papers “not found in PubMed” are included, others not : if the paper of Dubois, 2021 [119] is obviously relevant for the analysis and was included by Peters and Verhagen in their analysis, even if this study was not found on PubMed (it was published in a marketing review), it is surprising that other studies cited in Table 1, particularly relevant for the validation of Nutri-Score and Favourable to Nutri-Score (and published by authors without COI and without scientists of the research team that developped Nutri-Score) were excluded under the pretext they were… “not found on PubMed”. It is the case, for instance, of papers published by Crosetto et al, 2016 ; Crosetto et al , 2017 ; Crosetto et al 2019 [159], that are 3 incentivised laboratory framed field experiment examining the impact of different front-of-pack labels (Multiple Traffic Lights; Reference Intakes; HealthStarRating; NutriScore and Système d’Etiquetage Nutritionnel Simplifié) on food shopping. The 3 papers concluded on “the positive impact of Nutri-Score on the nutritional quality of food purchases and Nutri-Score is the most effective compared to other labels and not to intermediate values. Nutritional gains are not correlated with higher expenditure.”

In the same way the paper of Egnell et al (2019) cited in Table 1 as Favourable was excluded of the analyzed selection as it was… not found in Pubmed. Either the absence of a paper on PubMed was an exclusion criteria, or it was not. The inconsistency of the classification is a major methodological issue.

Thus, the inclusion and exclusion criteria of Peters and Verhagen’s paper are inconsistent and biased towards the inclusion of articles judged as not favourable to Nutri-Score.

Several papers Favourable to Nutri-Score (presented in the bibliography) have been excluded from the analysis since they are considered as not relevant for validation of Nutri-Score, whereas in fact they are totally relevant and should have been included in the analysis. It is the case of, at least, the following 7 papers:

* the paper by Batista, 2023 [121], an integrative review (performed by authors with no COI) Favourable to Nutri-Score as it concluded that “Interpretive schemes (such as warning labels, multiple traffic lights, and Nutri-Score) appear to lead to better consumer understanding and support healthier food purchases…

The exclusion of this paper cannot be related to the fact it is a review as 10 other reviews unfavourable to Nutri-Score (and performed by authors with COI), were considered in Table 1 relevant for validation of Nutri-Score and included in the analysis (see Table 2) : ref [4,5,73,76, 83, 93, 97, 98, 102, 103]

* the paper by Bossuyt, 2021 [108] an eye-tracking experiment and healthfulness estimations (performed by authors with no COI) Favourable to Nutri-Score as it concluded that “the results of the study confirmed the positive impact of the Nutri-Score on healthfulness estimation accuracy, though the impact was larger for equivocal (i.e., difficult to judge) products”.

* the paper by Egnell, 2018 [26], a randomized study aiming to investigate the impact of front-of-pack nutrition labels on 25,772 subjects (performed by authors of EREN with no COI) Favourable to Nutri-Score as “showing that Nutri-Score followed by MTL appear efficient tools to encourage consumers to decrease their portion size for less healthy products, while ENL appears to have inconsistent effects depending on the food category”.

* the paper by Fialon, 2022 [145], a randomized study (performed by author sof EREN with no COI) Favourable, concluding that “the interpretive format Nutri-Score appears in a group of italian consumers to be a more efficient tool than NutrInform for orienting Italian consumers towards more nutritionally favorable food choices”.

* the paper by Fialon, 2023 [167], a randomized study (performed by authors of EREN with no COI) Favourable providing “new evidence to support Nutri-Score in comparison with NutrInform in Spanish consumers, on both objective understanding and preference aspects”.

* the paper by Jansen, 2021 [112], a randomized controlled trial (performed by authors with no COI,) Favourable, concluded that “swap offer and Nutri-Score labeling were effective in enhancing healthy purchase behavior in the online store environment”.

* the paper by Jürkenbeck, 2022 [113]. This study (performed by authors with no COI), Favourable to Nutri-Score, analyzed if the Nutri-Score can help to prevent health-halo effects caused by nutrition claims on sugar using an online survey. The results showed that “depending on the initially perceived healthiness of a product, the Nutri-Score is able to prevent health-halo effects caused by claims on sugar. The mandatory introduction of the Nutri-Score, at least as a prerequisite for health marketing, could help to reduce problematic health effects caused by misleading claims”.

Some opinion papers (Favourable to Nutri-Score) are logically not taken into consideration as relevant for validation of Nutri-Score and not included in the analysis by Peters and Verhagen, but some are, such as the paper by Donini, 2023 [80], which is classified as “Review-opinion”, but is a not a scientific review but rather an opinion paper (and it is Unfavourable to Nutri-Score).

2. Misclassifications of papers as “Favourable / Neutral / Unfavourable” to Nutri-Score

Several papers are obviously misclassified (classified Neutral or Unfavourable whereas they are Favourable):

* The paper by Dubois, 2021 [119], a RCT supermarket trial comparing different labels and a no-label condition, is classified as Neutral, but in fact is Favourable. The conclusions of authors of this paper are “Nutri-Score is the best nutrition label, closely followed by Nutri-Couleurs, with SENS and Nutri-Repère significantly behind. Nutri-Score had the largest and the only statistically significant (at 10%) improvement in the nutritional quality of the basket of labeled products purchased, thanks to its positive impact on the purchase of high nutritional-quality products, followed by a monotonically decreasing effect on the purchases of products of medium and low nutritional quality. This last result is important given that other labels had the undesirable property of having a larger influence on products of medium quality than on products of low-nutritional-quality products. The shopper survey suggests that this happened because Nutri-Score is among the top two most visible labels but provides the easiest way to gauge the relative nutritional quality of the food…”

* The paper by Egnell, 2019 is classified as Unfavourable by Peters and Verhagen whereas it is Favourable. The conclusion of this 3-arm randomized controlled trial in students is: “the Nutri-Score label appeared to improve the nutritional composition of students’ food purchases relative to the Reference Intakes label or no label”.

Moreover Peters and Verhagen state in Table 1 that this paper of Egnell et al. with ref 70 is the same as that with ref 76. However, ref 76 is a narrative review published by Azais-Braesco, unrelated with the paper by Egnell et al.

* Another paper by Egnell, 2021 [161] is classified as Unfavourable whereas it is Favourable. The authors concluded that “this randomized trial in a low income population showed that the Nutri-Score resulted in the highest overall nutritional quality of the shopping cart, significantly higher than the RIs but not significantly higher than no label. The Nutri-Score also resulted into significantly lower contents in calories and saturated fatty acids in the shopping cart, compared with the RIs. Nutri-Score appears to have the potential to encourage purchasing intentions of foods from higher nutritional quality among low-income individuals, compared with the RIs label promoted by food manufacturers”.

* The paper by Finkelstein, 2019 [120] is classified as Neutral whereas it is Favourable : authors of this trial concluded that “both the MTL and Nutri-Score front-of-pack labels improved dietary quality according to the modified AHEI-2010, providing support for implementation of either label if the goal is to improve overall diet quality. Nutri-Score outperforms MTL and no FOP labels on average but Nutri-Score, unlike MTL, does not reduce calories, suggesting that MTL may be preferred to NS if the goal is to reduce caloric intake and obesity rates”.

* The paper by Fuchs, 2022 [82] is classified as Unfavourable whereas it is Favourable. Authors concluded that “providing an interpretive FoPL (i.e., the Nutri-Score) in an established online supermarket can increase the nutritional quality of food products chosen by consumers according to the HETI. This result provides additional support for the wide-spread implementation of such labels. This is especially emphasized as we found no difference in effects between participants with low and high levels of food literacy. Finally, we found that providing Nutri-Score labels in a real online supermarket led to positive consumer perceptions and higher general approval ratings regarding its implementation”.

* The paper by Julia et al, 2015 [140] is classified as Neutral whereas it is Favourable. The authors concluded that “the 5-CNL label (first graphical version of the Nutri-Score) displays a high performance in discriminating nutritional quality of foods across food groups, within a food group and for similar products from different brands”.

* The paper by Hafner, 2021 [141] is classified as Unfavourable whereas it is Favourable. The authors showed that “both the Nutri-Score and HSR profiling models have good discriminatory abilities and are in very good alignment for most prepacked foods in the Slovenian food supply. Notable differences were observed in some subcategories, particularly in Cheese and processed cheese and Cooking oils”.

* The paper by Hafner, 2021 [142] is classified as Unfavourable whereas it is Favourable. The conclusion of authors is that “the Nutri-Score has a good ability to discriminate among food products not only between but also within categories. This ability is aligned with the national nutrition policy programme and has moderate agreement with the nationally accepted WHOE profile”.

* The paper by Shrestha et al, 2023 [98], is classified as Unfavourable whereas it is Favourable. The authors of this systematic review concluded that “simplified and easy-to-understand FOPLs such as Nutri-score and traffic light labelling are likely to be effective for all populations including low SES groups”.

* The paper by Ter Borg et al , 2021 [99] is classified as Unfavourable but it is not. Its most conservative assessment would rather be Neutral but it is mainly Favourable as the authors concluded that “the Nutri-Score classification is in line with the Dutch food-based dietary guidelines: increase the consumption of fruit and vegetables, pulses, and unsalted nuts. It is however less in line with the recommendations to limit (dairy) drinks with added sugar, to reduce the consumption of red meat and to replace refined cereal products with whole-grain products. In our scenario analyses, decreasing the sodium, saturated fat or sugar content by one Nutri-Score point resulted in certain products (e.g., composite dishes, cereals, milk products) shifting towards a more favourable Nutri-Score (ranging from about 0–30%). Nutri-Score may therefore be an incentive for reformulation of certain foods. Alterations to the algorithm may strengthen Nutri-Score in order to help consumers with their food choices”.

* The paper by Vandevidjere (ref 100) is classified Unfavourable while the study does not test the coloured Nutri-Score displayed of front-of-packs but the impact of electronic shelf labels on all food products in-store on consumer food purchases, but unlike the Nutri-Score on the food packages, the electronic shelf labels are in black and white.c

* The paper by Besançon et al [ref 6]is classified by the authors as Neutral (in fact it is obviously Favourable concluding that 83% of the papers concerning Nutri-Score had conclusions favourable to this label demonstrating the relevance of its algorithm, better performances vs other nutrition labels, an impact on food choice and on the nutritional quality of food purchases).

3. Errors in the number of studies included and inconsistencies between text and tables

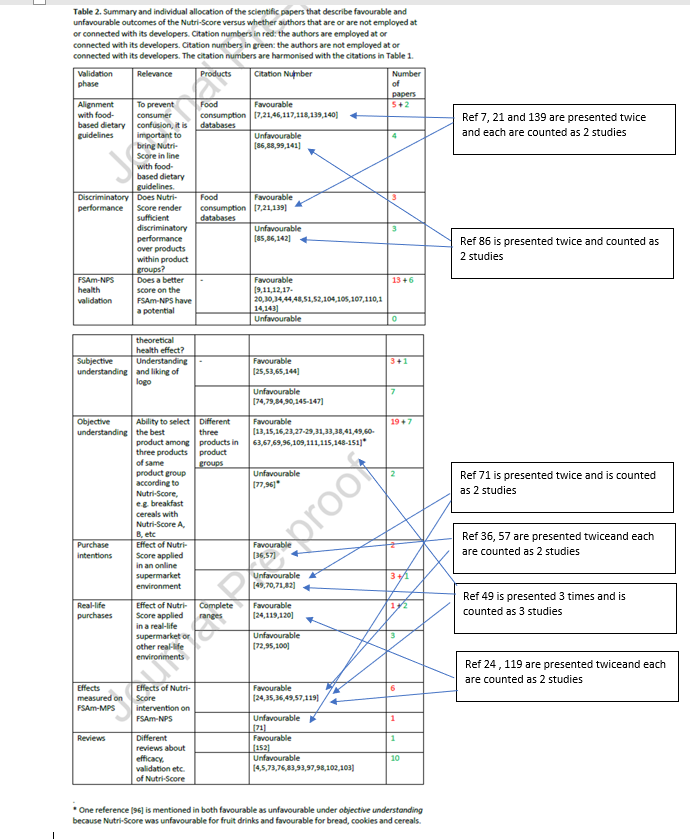

When we check the tables and the text, we can find many inconsistencies and several errors regarding the number of scientific papers considered as relevant for the analysis and concerning the classification of papers. In the Table 2, several papers are counted twice (and even three times) and there are some discrepancies between text and tables. It is indicated in the text and in the tables that the total number of relevant references is n=104. But in fact, this figure does not match the description in the text.

In the text, authors state that a total of 180 papers were identified, of which n=104 addressed some kind of validation of the Nutri-Score system. This is also indicated in Figure 1: Prisma Flow Diagram for review Nutri-Score search based on Pubmed search July 22nd 2023.

In both text and tables, authors refer to 104 article and they base their count on the presentation of Table 2. When adding the total of papers presented in Table 2, we find 105 papers; the authors has explained that one reference [96] is mentioned in both favourable and unfavourable to objective understanding because Nutri-Score was unfavourable for fruit drinks and favourable for bread, cookies and cereals.

If paper 96 appears twice and is logically counted by the authors as only 1 study, we can see below in Table 2 when we check all the references that 9 articles are presented twice (ref 7, 21 24, 36, 57, 71, 86, 119, 139) and are counted each for 2 different studies and even one article is presented 3 times (ref 49) and counted as 3 studies ! Finally there are not 104 different studies analyzed but only 93 (see Table below).

Thus, contrary to what the authors claim in the text and in the Table 2, Peters and Verhagen did not select 104 articles but 93 different papers;

This point, in addition to the classification errors, has major consequences on the actual results of their data. Indeed, of the 10 articles presented 2 or 3 times, what is highly misleading is that 8 are articles published by the team that developed Nutri-Score, giving the impression that the latter published more studies than what they actually published and skew the results in the direction of the erroneous message that Peters and Verhagen want to convey…

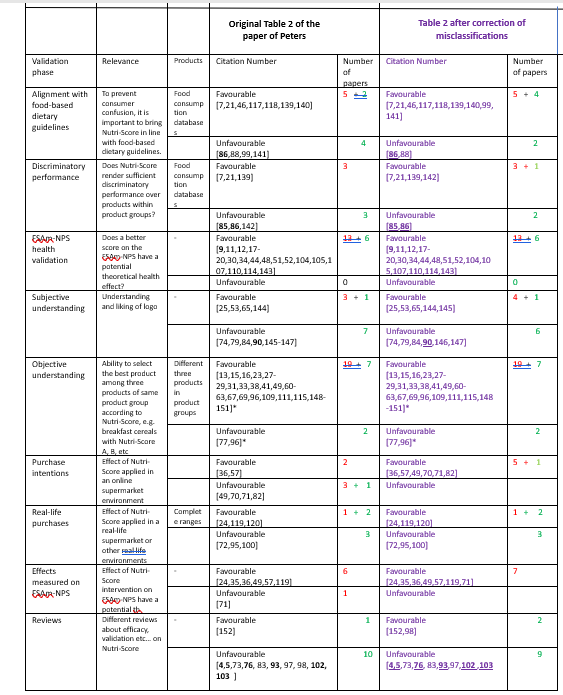

After correction of these points, the real results are not those the authors present in their paper.

Moreover, if we correct the misclassifications of some papers made by the authors concerning the classification of scientific papers as “favourable” or “unfavourable” to Nutri-Score, results of the review are different.

In the table below the original table 2 of the Peter and Verhagen’s paper (same as above) is presented with the classification they used. Besides we have added, to the right side, the same table (citation numbers in blue) after correction of the classification errors.

According to Peters and Verhagen’s classification, the citation numbers in red correspond to papers published by scientists “employed at or connected with its developers” (terms used by Peters and Verhagen). Citation numbers in green: the authors are not “employed at or connected with its developers” (terms used by Peters and Verhagen).

We add a crucial indication (not presented in the paper of Peters and Verhagen). We used bold characters to indicate if the authors of the papers declare a conflict of interest (COI) or if the study is funded by the food industry. After checking the papers, we found 11 papers that included declarations of a conflict of interest or indicated that the authors had received funding from the food industry: 10 in the group of papers classified as unfavourable to Nutri-Score and 1 in the group of paper classified as favourable to Nutri-Score (see below).

| TOTAL | 105 | 105 |

4. Errors on the main conclusions of the paper needing to be corrected

Finally the main result of the paper of Peters and Verhagen presented in Table 3 has to be corrected. See below:

Initial Table 3 in the paper of Peters and Verhagen

| “Authors that are or are not employed at or connected with its developers” | ||

| “Employed or connected” | “Not employed or connected” | |

| Favourable | 52 | 19 |

| Unfavourable | 4 | 30 |

Same Table 3 after correction for the misclassifications (according to corrected Table 2, see above), with information on conflict of interests (COI)of authors and/or funding by agro-alimentary sectors

| “Authors that are or are not employed at or connected with its developers” | ||

| “Employed or connected” | “Not employed or connected” | |

| Favourable | 57 (1 COI) | 24 (0 COI) |

| Unfavourable | 0 | 24 (11 COI) |

Same Table 3 after correction of the misclassifications and after counting only once, the papers presented twice or 3 times in Table 2 by Peters and Verhagen (and with information on conflict of interests (COI) of authors and/or funding by agro-alimentary sectors)

| Authors that are or are not employed at or connected with its developers | ||

| Employed or connected | Not employed or connected | |

| Favourable | 49 (1 COI) | 20 (0 COI) |

| Unfavourable | 0 | 24 (10 COI) |

Finally of the 93 articles selected by Peters and Verhagen, 69 (74,2%) are favourable to the Nutri-Score and 24 of the 93 articles (25,8%) had results not favourable to the Nutri-Score (among them, 9 were reviews, not original studies).

Of the 69 studies considered favourable to the Nutri-Score, only one (1,4 %) included declarations of a conflict of interest or indicated that the authors had received funding from a structure linked to food company. Conversely, 10 of the 24 studies presenting results which are unfavourable to Nutri-Score (41.7%) included a conflict of interest by the authors or had received funding from food professional organizations defending the interest of food companies or agro-food sectors (such as the Dutch Dairy Association, the Italian Nutrition Foundation, Federalimentare…).

The probability for an article to show results that are unfavourable to Nutri-Score is 33 times higher for papers funded by the food industry or published by authors declaring a conflict of interest.

Peters and Verhagen do not present these results in their paper. They prefer to focus on academic research teams trying to suggest that they have a conflict of interest (it is the term they used in the Table 1).

5. Biaised definition of conflicts of interests

Denying the economic conflicts interests behind papers with unfavourable results about Nutri-Score, Peters and Verhagen only choose to disqualify papers showing favourable results for Nutri-Score published by the academic researchers that developed Nutri-Score and performed validation studies only with public funds, and sometimes in collaboration with other academic research teams or public structures (WHO, IARC, George Institute, Oxford University, Tarragona University…). Peters and Verhagen try to discredit these studies considering that they would present bias / « conflicts of interest » even if the academic research team that has participated in the development and validation of the Nutri-Score is composed by independent experts from the National Institute of Research or University, working extensively on the subject of front-of-pack labels for several decades and on many other public health topics regarding the relationships between nutrition and health. Casting suspicion on the ethical practices of academic research teams is offending for researchers that are experts in the field developing their research without any economic profits but only working for public health ! It is clear that to minimize the fact that they defend economic interests, authors suggest that academic researchers who developed Nutri-Score and even academic research teams associated in some studies have conflicts of interest. Using this fallacious definition they classify the articles in a way to support the economic interests of their employer/clients in the food industry.. It is all the more absurd that if this bias had any basis in reality, the Australian or New Zealan co-authors should have been suspected of attempting to skew results in favour of ethe HSR existing in their countries, or the UK authors in favour of MTL as there is no reason to expect/assume they would have supported the results being pushed in favour of Nutri-Score !

We are really surprised and even concerned by the tone and the false arguments laid in the discussion of the paper of Peters and Verhagen. It is full of innuendos, harsh attacks and fake news on academic research teams and discredit with wrong arguments the results of real scientific papers published in well-known international scientific journals. The text suggests at times scientific misconduct on the part of academic research teams. This is very shocking and very far from any fair scientific debate.

They criticize not only the research team (EREN) that developed on a scientific basis, Nutri-Score, but all the academic research teams who were associated in the framework of scientific collaborations to develop studies aiming to compare in different contexts, different front-of-pack nutritional labels: Australian and New-Zealand Health Star Rating, UK Multiple Traffic Lights, Chilean Warning labels, RIs/GDA, SENS…

These independent research teams were considered “affiliated or employed by EREN” which is simply untrue.

Unlike industry lobbies like the Dutch Dairy Association, that advocates for the interests of dairy companies, the academic research team (not « Nutri-Score developers ») and the collaborative research teams all around the world who have worked on nutrition labels leading to the choice of Nutri-Score and/or its validation have no interest other than that of public health.

Faced with science, with this totally biased paper, Peters and Verhagen try to dilute the fact that they eventually defend financial interests, suggesting that the research team whose scientific works have permitted to propose Nutri-Score should be disqualified to perform new studies on the topic. As they are doing today with Nutri-Score, food lobbies will also accuse under the same pretext the Brazilian scientists who developed the NOVA classification for continuing to perform studies on Ultra Processed Food or the Chilean colleagues for doing studies on the Warnings labels. This is non-sense and a classic lobbying strategy.

This kind of non-scientific papers with many errors and biases, written by 2 lobbyists has no place in a scientific journal.

Beyond the question of Nutri-Score here, this is the ethics of research and science that is at stake.

======================================================

ADDENDUM

How it is possible that this paper written by lobbyists full or errors, imprecisions, biased arguments, harsh accusations and insinuations of scientific misconduct against academic researchers, denial of economic COI, erroneous conclusions… could be published in a scientific journal (PharmaNutrition) ?

Just a note : the editor is Francesco Visioli from the Padova University.

Francesco Visioli has taken public positions against Nutri-Score, especially in events organized by structures close to lobbies such as Competere*

For example, in a recent webinar reported by the media European Scientists (https://www.europeanscientist.com/en/editors-corner/eu-council-presidency-what-will-france-do-with-its-nutri-score/), Francesco Visioli from the University of Padova debating with Ramon Estruch from the University of Barcelona (another opponent to Nutri-Score) on the scientific basis of Nutri-Score came to the conclusion that “there was nothing scientific about the label, and that it jeopardized consumer choice by misleading consumers”. “The algorithm used by the Nutri-Score is arbitrary and can be easily manipulated. The proof: healthy foods from the Mediterranean diet are poorly rated. On top of that: “the nutrients contained in the food are evaluated in an arbitrary way;” in fact, processed foods are favored because their ingredients can be modified. Finally, it is the overall diet that should be considered in terms of dietetics, and not the types of comparisons between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ foods that Nutri-Score makes by distributing scores. As such, these experts prefer and recommend a Nutrinform-type solution that simply informs consumers and gives them a tool that empowers them to choose for themselves, instead of infantilizing them”.

And a press release (https://www.competere.eu/press-release-the-european-scientific-community-against-nutriscore/):

Milan, November 16, 2021 – Reaffirming the anti-scientific nature of NutriScore, demonstrating the lack of scientific basis of the arguments supporting the measure and stressing consolidated studies that have always highlighted the weaknesses and threats of the NutriScore.

This is the mission launched during the conference “Science Vs Ideology – Beyond NutriScore” organized by Competere.eu, the European think tank and promoter of the only Italian platform for a scientific discussion on sustainable nutrition, which saw the participation of two prestigious scientists, Dr. Francesco Visioli from the University of Padova and Dr. Ramon Estruch, from the University of Barcelona.

The discussion showed how the NutriScore system is based on non-scientific elements, thus jeopardizing the ability of consumers to identify the correct diet to follow and their freedom of choice.

Why is NutriScore not scientifically valid? These are some of the main points that have emerged:

• The algorithm used by NutriScore is arbitrary and can be easily manipulated, generating the paradox that healthy foods such as those part of the Mediterranean Diet would turn out to be harmful.

• The nutrients contained in foods are evaluated in an arbitrary manner, leading companies to modify ingredients in order to obtain higher scores and favoring highly processed foods.

• The proposed distinction between positive and negative foods goes against the scientific literature, leaving out the impact of the nutrient within the overall diet.

“NutriScore is not based on the results of scientific studies. It contains many flaws as it mixes energy, food and nutrients, it does not evaluate the quality of proteins, fat or carbohydrates and it does not highlight positive aspects such as high density of nutrients – mineral and vitamins – or content in bioactive compounds. Lastly, it does not take into account the degree of processing” – affirmed Dr. Ramon Estruch from the University of Barcelona.

“NutriScore presents an approach that goes against the indications of the vast majority of nutritionists. It focuses on individual foods and nutrients instead of the concept of diet; it disregards the concept of portions, preferring the indication of values per 100g; it does not help the consumer to understand which nutrients can be positive or negative. In this way olive oil gets a lower score than a soft drink” – said Dr. Francesco Visioli from the University of Padova.

The information provided by NutriScore is also misleading for consumers, heavily restricting their ability to choose. The NutriScore judges foods without providing any direct nutritional information (composition, nutrient content, etc.): the consumer cannot know why a food is classified as positive or negative. In addition, people with special dietary needs have no support from NutriScore.

According to some research, consumers in seven European countries (France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Romania, and Spain) prefer the detailed Nutrinform Battery labeling system over NutriScore. (Mazzù et al., 2020, 2021) It is demonstrated that many consumers are suspicious of summary labels that do not show nutritional information, (Grunert and Wills, 2007; Hodgkins et al., 2012) preferring instead labels that are intended to educate, stimulate critical thinking and understanding of individual needs.

“Competere represents the only Italian subject and one of the few in Europe to promote a scientific, rigorous and super partes debate on NutriScore, acting as a driving force and collector of scientific contributions generated by the most prestigious European scholars. Today we have once again highlighted the lack of scientific basis of the NutriScore, as it only aims to arbitrarily condemn or promote foods while it does not educate the consumer, forcing him towards choices based on incomprehensible and non-transparent parameters. NutriScore, in addition to generating paradoxical classifications of foods that are symbols of the Mediterranean Diet – scientifically considered as among the healthiest nutritional regimes in the world – represents a totally unscientific measure that jeopardizes not only a priceless social and economic heritage such as the Made in Italy agri-food, but also the wellbeing of European citizens” – affirms Pietro Paganini, Founder and President of Competere – Policies for Sustainable Development.

* Competere indicates on its website (https://www.competere.eu/partners/) among its partners that are known opponennts to Nutri-Score : Confagricoltura, European Palm Oil Alliance… And R Estruch et F Visioli are members of their scientific committee

=========================================================

This text is supported by these scientists (alphabetical order):

First signatories:

Andreeva V (Nutritional Epidemiology Research Team, Inserm/Inrae/Cnam/Sorbonne Paris Nord University, France), Deschasaux-Tanguy M (Nutritional Epidemiology Research Team, Inserm/Inrae/Cnam/Sorbonne Paris Nord University), Galan P (Nutritional Epidemiology Research Team, Inserm/Inrae/Cnam/Sorbonne Paris Nord University, Hercberg S (Nutritional Epidemiology Research Team, Inserm/Inrae/Cnam/Sorbonne Paris Nord University), Julia C (Nutritional Epidemiology Research Team, Inserm/Inrae/Cnam/Sorbonne Paris Nord University), Karpetas G (Faculty of Medicine, School of Health Sciences, University of Thessaly, Greece), Kesse-Guyot E (Nutritional Epidemiology Research Team, Inserm/Inrae/Cnam/Sorbonne Paris Nord University), Kontopoulou, L (Nursing Department of the University of Thessaly, Greece), Monteiro C (Department of Nutrition, School of Public Health University of Sao Paulo, Brazil) Pettigrew S (Faculty of Medicine, The George Institute for Global Health, Sydney, Australia), Pravst I (Nutrition Institute, Ljubljana, Slovenia), Ravaud Philippe (Centre de Recherche en Epidémiologie et Statistiques, Université de Paris, France), Salas-Salvado Jordi (Human Nutrition Unit, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Reus, Spain), Mauro Serafini (Faculty of BioSciences and Technology for Food, Agriculture and Environment, Teramo University, Italy), Srour B (Nutritional Epidemiology Research Team, Inserm/Inrae/Cnam/Sorbonne Paris Nord University), Touvier M (Nutritional Epidemiology Research Team, Inserm/Inrae/Cnam/Sorbonne Paris Nord University)